Impute.

Dispute.

Statute.

Refute?

No.Execute.

Impute.

Dispute.

Statute.

Refute?

No.Execute.

Ruined man always chose lesser evils.

I think about this sometimes.

If all of your choices seem bad, and you feel as though you’re always choosing between two evils and picking the lesser, eventually the lesser evil ruins you, too, though maybe not as quickly as the greater one would have. Most people at some point go through periods of their life where our options seem to be this way.

Ex: If Jim works all the time, he can pay his expenses but never sees his wife and kids. If Jim doesn’t work all the time, he sees his wife and kids but can’t pay his bills.

What do you do in an untenable situation?

Forgive the bad language:

Here’s a more family friendly answer to that same scenario:

In antiquity, this was a “Gordian Knot” situation. (via wiki)

The cutting of the Gordian Knot is an Ancient Greek legend associated with Alexander the Great in Gordium in Phrygia, regarding a complex knot that tied an oxcart. Reputedly, whoever could untie it would be destined to rule all of Asia. In 333 BC, Alexander was challenged to untie the knot. Instead of untangling it laboriously as expected, he dramatically cut through it with his sword. This is used as a metaphor for using brute force to solve a seemingly-intractable problem.

Turn him to any cause of policy,

The Gordian Knot of it he will unloose,

Familiar as his garter— Shakespeare, Henry V, Act 1 Scene 1. 45–47

Legend

The Phrygians had no king, but an oracle at Telmissus (the ancient capital of Lycia) decreed that the next man to enter the city driving an ox-cart should become king. A peasant farmer named Gordias drove into town on an ox-cart and was immediately declared king. Out of gratitude, his son Midas dedicated the ox-cart to the Phrygian god Sabazios (whom the Greeks identified with Zeus) and tied it to a post with an intricate knot of cornel bark (Cornus mas). The knot was later described by Roman historian Quintus Curtius Rufus as comprising “several knots all so tightly entangled that it was impossible to see how they were fastened”.

The ox-cart still stood in the palace of the former kings of Phrygia at Gordium in the fourth century BC when Alexander the Great arrived, at which point Phrygia had been reduced to a satrapy, or province, of the Persian Empire. An oracle had declared that any man who could unravel its elaborate knots was destined to rule over all of Asia. Alexander the Great wanted to untie the knot but struggled to do so before reasoning that it would make no difference how the knot was loosed. Sources from antiquity disagree on his solution. In one version of the story, he drew his sword and sliced it in half with a single stroke. However, Plutarch and Arrian relate that, according to Aristobulus, Alexander pulled the linchpin from the pole to which the yoke was fastened, exposing the two ends of the cord and allowing him to untie the knot without having to cut through it. Some classical scholars regard this as more plausible than the popular account. Literary sources of the story include Arrian (Anabasis Alexandri 2.3), Quintus Curtius (3.1.14), Justin‘s epitome of Pompeius Trogus (11.7.3), and Aelian‘s De Natura Animalium 13.1.

Alexander the Great later went on to conquer Asia as far as the Indus and the Oxus, thus partially fulfilling the prophecy.

Interpretations

The knot may have been a religious knot-cipher guarded by priests and priestesses. Robert Graves suggested that it may have symbolised the ineffable name of Dionysus that, knotted like a cipher, would have been passed on through generations of priests and revealed only to the kings of Phrygia.

Unlike popular fable, genuine mythology has few completely arbitrary elements. This myth taken as a whole seems designed to confer legitimacy to dynastic change in this central Anatolian kingdom: thus Alexander’s “brutal cutting of the knot … ended an ancient dispensation.”

The ox-cart suggests a longer voyage, rather than a local journey, perhaps linking Alexander the Great with an attested origin-myth in Macedon, of which Alexander is most likely to have been aware. Based on this origin myth, the new dynasty was not immemorially ancient, but had widely remembered origins in a local, but non-priestly “outsider” class, represented by Greek reports equally as an eponymous peasant or the locally attested, authentically Phrygian in his ox-cart. Roller (1984) separates out authentic Phrygian elements in the Greek reports and finds a folk-tale element and a religious one, linking the dynastic founder (with the cults of “Zeus” and Cybele).

Other Greek myths legitimize dynasties by right of conquest (compare Cadmus), but in this myth the stressed legitimising oracle suggests that the previous dynasty was a race of priest-kings allied to the unidentified oracular deity.

In truth, most of the time, we have more than two options. If the only options we can see look like bad ones, it might be time to ask someone else what they can see (or, as Kirk would put it, you change the conditions of the test.) Otherwise… eventually those lesser evils will defeat us as surely as the greater ones.

Ancestry.com genetic testing reveals Grandmother’s affair.

This is apparently a real thing .

A not completely negligible number of people have found out through sites like 23andMe and Ancestry that the person they thought was their cousin was actually their half-brother. Or that their sibling is actually their half-sibling and so is the neighbor down the street. I can’t imagine being 85 years old, thinking that you’ve almost made it to the grave with your secrets, and then everything comes out into the open because your grandkid wanted to know which type of European they are.

___________________________

The Dark Side of DNA: How Genetic Tests Expose Family Secrets (And Why They’re Not Perfect)

If you’re curious about your heritage, you can always take one of those trendy DNA tests. Sites like 23andMe and AncestryDNA offer users the opportunity to take a closer look at their genetics, and by all accounts, they’re largely accurate. There’s no easier way to find out if you truly have Scandinavian heritage, or if you’re Irish enough to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day guilt free. In 2017 alone, about 12 million Americans purchased genetic genealogy tests. That means around 1 out of every 25 American adults have access to detailed genetic information—and, by all accounts, that number is going up. However, there’s a dark side to online genetic tests: They occasionally unearth uncomfortable information. In fact, the major DNA testing sites explicitly warn their users about that possibility. “You may discover unexpected facts about yourself or your family when using our services,” Ancestry.com’s privacy page warns. “Once discoveries are made, we can’t undo them.” Granted, these situations are rare, but when they occur, they have life-altering consequences. We looked into a few cases where people received results they weren’t expecting (and what happened next).

Liane Kupferberg Carter met her husband Marc during a vacation in Nassau. It was a storybook romance—or, as she described it in a piece for The Cut, “rom-com cute.” “I was 25; he was two years older,” she wrote. “Initially, he was chasing my roommate. We struck up an intense conversation on the plane home, and by the time we landed at JFK, I had the unbidden thought, ‘I could marry a guy like this.’” Spoiler alert: She married him. After arriving home, Liane discovered that Marc lived one block away from her Manhattan apartment. Flash forward a few years, and they were planning their lives together. They tied the knot, and everyone lived happily ever after. https://www.instagram.com/p/BSbz-HRgSA_/ Well, sort of. 38 years later, Liane signed up for 23andMe, and one day, she received an email: “You have new DNA relatives.” The relative in question was her husband, Marc. He was her third cousin. Before you get all creeped out, it’s important to know that third cousins don’t have a significantly higher risk of birth abnormalities than totally unrelated people. In fact, one Icelandic study showed that third- or fourth-cousin couples tend to be well suited biologically and typically have more kids than other couples. There’s even some research suggesting that first cousins’ risks are only a few percentage points higher than other couples (and cousin marriage was fairly common throughout history—Albert Einstein, Charles Darwin, and Edgar Allan Poe all married their cousins, and we certainly don’t look at them like they’re rogue Game of Thrones characters).

Albert Einstein & his wife Elsa in 1919. They were first cousins. pic.twitter.com/rerfwrQEro

— History In Pictures (@HistoryInPics) April 27, 2019

One of Carter’s children has an epileptic disorder and autism, but there’s no clear link between the couple’s genetic similarity and the boy’s conditions. While Liane admits that her unexpected genealogical revelation gave her some pause, she never doubted that her husband was the right man for her. “I don’t need the imprimatur of 23andMe to tell me what I already know with bone-deep certainty: our connection is a decades’ long conversation that continues to nurture and sustain us both,” she wrote. In other words, she’s, uh, glad she married her cousin.

Linda Ketchum of Glendale, California received an AncestryDNA test from her husband as a Christmas present. Per a report in The New York Post, she wasn’t expecting much; she simply wanted to trace back her heritage. “My dad was German, and my mother was Scottish-English,” she told the paper. “I thought it’d be fun to learn a little about my genetic ethnicity, to trace how all the pieces came together.” Unfortunately, the results were fairly dramatic. Ketchum discovered that she had no biological link to her father whatsoever. Instead, she had numerous connections to Hispanic people in the site’s database. “At first I didn’t believe it,” she said. “But then I kept re-checking it, and I realized, ‘Oh my God, does this mean I’m…I’m Hispanic!’” Her real biological father was a man of Hispanic descent. As both of her parents were deceased, she had nowhere to turn for answers. “All these years I thought I was German on my dad’s side, but all of a sudden it was dawning on me that my dad wasn’t my real dad and I had an entirely different ethnicity.” Ketchum told the paper that she was fairly traumatized. She lost her identity, and she began wondering whether she was related to random Hispanic people she saw on the street. She eventually tracked down her real biological father, Bill Chavez, who lived in New Mexico. He had also passed away, so she wasn’t able to connect with him. Ketchum’s story doesn’t have a happy ending, per se, but she’s at peace with the discovery. Still, she frequently thinks about the family she never met. “I still wonder sometimes, would my life have been different if I’d known this earlier?” she said. “My real father, my actual grandparents, they all spoke fluent Spanish. I can’t even speak a word of it!”

Journalist Bill Griffeth took a DNA test in 2012, hoping to learn more about his European ancestors. He’d had an ongoing interest in genealogy—he’s on the board of Boston’s New England Historic Genealogical Society—and he had even written a book about his ancestors’ journey to the United States. Griffeth was extremely proud of his family, and when his cousin asked him to participate in genetic testing to get more information about their family origins, he happily agreed.

Hey, he’s part of this article, so you probably know where this is going. The test showed that Griffeth had no biological relation to his late father. When he received word via email, he was crushed. “My body responded before my brain could,” Griffeth wrote in his memoir The Stranger in My Genes. “I experienced a strange sensation of floating, and I could no longer feel the chair I was sitting in or the Blackberry I was holding. My breathing became labored and shallow and I heard a roaring in my ears like ocean waves crashing off in the distance.” Initially, Griffeth denied the results, insisting that the company that tested his DNA had made some mistake. He actually went on the air on CNBC within hours of receiving the news and acted as though nothing had happened. For months, he refused to accept reality. Eventually, the truth set in: His mother had had an affair, which she’d hidden from her family for decades. He eventually decided to confront her with the information.

“There was a time when I said, ‘I don’t want to pursue this any further, I don’t want to trouble Mom with it,’” Griffeth told the Extreme Genes podcast. “But as my brother said, ‘What if you want answers eventually and she’s gone, what are you going to do? And what about your children, they’re going to need answers down the road?’” “We really needed to know the truth, so I presented her with the DNA evidence, and she took it like a champ. She admitted that she had made a mistake when she was younger, and that was that.” These days, Griffeth is at peace with his family history. He doesn’t discuss the matter with his mother, but when he decided to write a book about his experience, she gave him her blessing.

This was released 3 years ago today. Since then, so many people have reached out to me with similar stories. I’ve made some lasting friendships. As one friends has said, you don’t get over a shocking DNA test result, but you get through it. Cheers to my fellow DNA club members. pic.twitter.com/iIsy66Mxh0

— Bill Griffeth (@BillGriffeth) August 20, 2019

“We don’t talk about it anymore,” he said. “…She’s of a different generation, a different time.” Since going public with his story, Griffeth has heard from dozens of people about their own DNA testing mishaps. He says his perspective has gradually changed; he knows if his mother hadn’t made her “mistake,” he wouldn’t be here, and he takes comfort in knowing his situation isn’t unique. “The only takeaway I can have from this is to be grateful about it,” he said. “…I encourage anybody, if you’re going through this, reach out. It’ll be a difficult first step, but you gotta be able to tell somebody.” “I just think that DNA testing is going to have a profound impact, not only on biotechnology and medicine—it’s already having an impact there—but I think it’s going to have a profound impact on our social culture.”

While many people get DNA tests to learn about their hereditary history, some choose to get tested for medical reasons. Certain hereditary conditions have genetic markers that can help doctors diagnose, prevent, and even cure diseases before they become life threatening. In fact, many direct-to-consumer DNA testing services like 23andMe offer specialized tests for these genetic markers—but they warn that people shouldn’t make medical decisions based on their screenings. Maureen Boesen has a family history of cancer, and she and her two sisters entered a university study to determine whether or not they had a BRCA gene mutation that would raise her risk of developing the disease. Boesen tested positive.

“It was just devastating because I knew what breast cancer and ovarian cancer can do to a family,” she told KSHB in Kansas City. “The first question out of my mouth was, ‘Is there any chance this could be wrong?’ And the researcher said ‘No.’” To limit her chances of developing cancer, Boesen underwent a preventive double mastectomy at 23. Years later, she also decided to undergo a complete hysterectomy, but prior to that procedure, doctors performed another test.

“I was at work, and the first thing [the doctor] said was, ‘We need to talk,’” she recalled. “And my heart just sank. And she said, ‘You’re negative!’ and I just started bawling. I was angry. I was regretful. I was happy. I was sad.” According to the U.S. Preventive Service Task Force’s recommendations for BRCA testing, doctors should screen some women with cancer in their family histories, but false positives occur occasionally. It’s unclear why Boesen’s physicians didn’t re-test her before carrying out her double mastectomy, but her story is a good indication of how genetic tests can be misleading—and why a second opinion is always helpful when making serious medical decisions. “I wish what I had been told was, ‘If you don’t trust it, get another test,’” Boesen said. “But that’s not what I was told, and my life could have been so different.”

Kristen Brown received a shock when her aunt sent off for a commercial DNA test: According to the results, Brown’s grandfather wasn’t a full-blooded Syrian. That led to a small family scandal. “If we weren’t who we thought we were, well, then, who were we?” Brown wrote for Gizmodo. But to Brown, something didn’t seem right. She suspected that the test was inaccurate, so she mailed DNA samples to three major commercial DNA testers…and received extremely different results from each. She’s not the only one. In 2018, reporter Rafi Letzler took nine DNA tests from three companies and received six distinctly different results. Even when a single company performs a test multiple times, the results can change dramatically. How could that happen? For starters, those heritage estimates (think “you’re 9 percent Scandinavian” and other such results) are just that—estimates—and they’re not as accurate as you might assume. To determine users’ heritage, sites compare the DNA of all of the people who’ve already taken the test. If a person’s genetic makeup is more similar to, say, the DNA of Scandinavian users, the service will conclude that the user has some Scandinavian heritage. However, the services can only work with whatever data is available. Heritage estimates will vary from one site to the next—if the site has a lot of Italian users, it’s more likely to provide accurate heritage estimates for people with Italian backgrounds, and conversely, if the site’s database doesn’t have many Middle Eastern samples to use as a comparison point, it will have trouble accurately determining the heritage of a person with a Middle Eastern background. “Your DNA is only part of what determines who you are, even if the analysis of it is correct,” Brown wrote. “…If the messaging of consumer DNA companies more accurately reflected the science, though, it might be a lot less compelling: Spit in a tube and find out where on the planet it’s statistically probable that you share ancestry with today.” That’s not to say that commercial genetic tests are worthless; they can provide some useful information about heritage, and they can accurately determine relationships between different users. But if you assume that the tests are perfect, the results are in: You’re 99 percent naive.

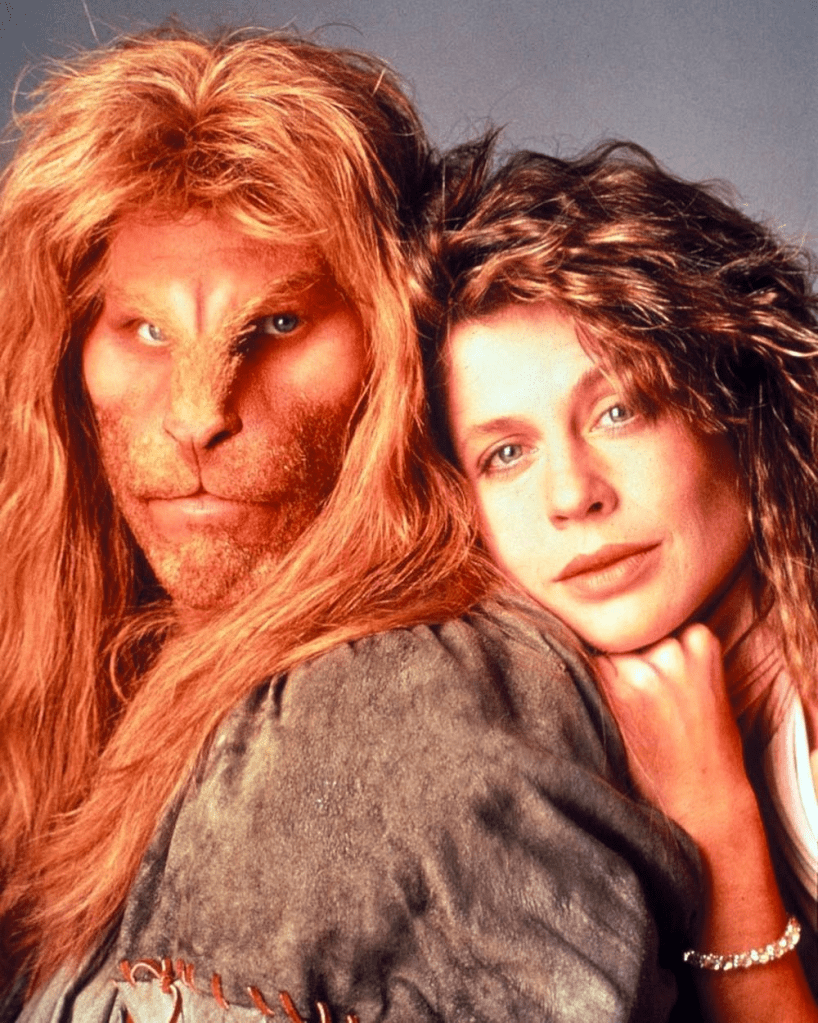

She repaired him; he outgrew her.

__________________________

This is an interesting relationship phenomenon. In my opinion, it’s a dangerous emotional undertaking to set out to “fix” someone. If you succeed, the person you end up with isn’t the one with whom you started. That could lead to anything. And yet decades of rom coms and romance stories have taught me that the beauty always wants to find a fixer-upper beast. Maybe the relationship is better off if the beauty finds the beast and just leaves him a beast? Or if she tries and fails to fix him?

OR… maybe the beauty inspires the beast, but ultimately the beast has to fix himself? If he does that himself, then maybe the relationship power dynamics don’t end up wonky and off-balance. I don’t know. I don’t think anyone knows.

Therapist: “There was a second date?”

__________________________

Sometimes people are in therapy for a reason and that reason is themselves.

At one time, I harbored an idea (not quite an ambition) to be a therapist. I kept finding myself in situations wherein I was giving advice and I was doing it for free. But I eventually decided that I might not be well-suited for the profession.

I care about people, once forced into it, but I also tire of them quickly so I try to avoid that.

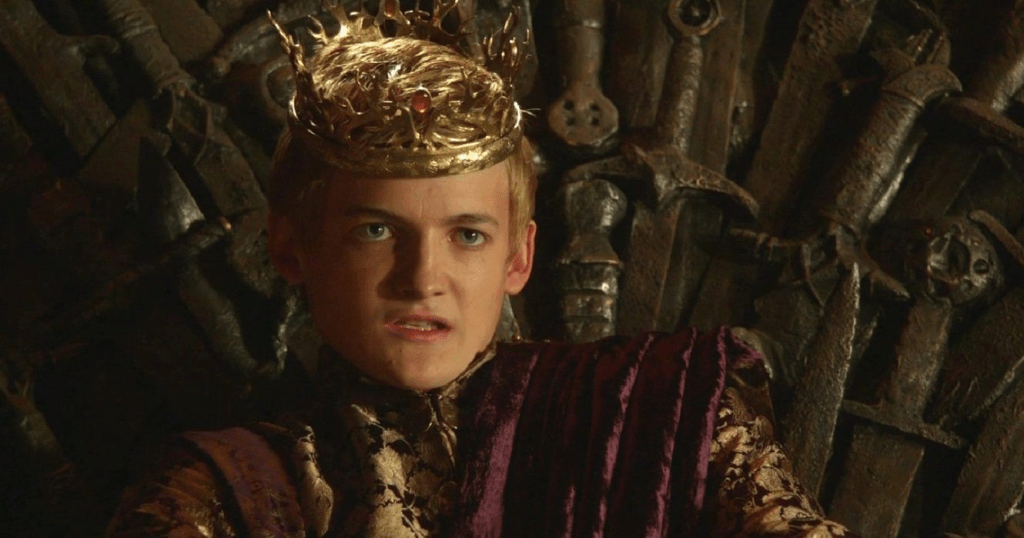

Everyone lives with the king’s mistakes.

__________________________

It’s a heavy burden to be in charge. Or, at least it should be. I assume anyone who wants to be in charge is either a dangerous megalomaniac or forced into the role to prevent a bad person from seizing power.

I also wonder if the people in those roles even know which of the two types they are. It’s an easy lie, to tell yourself and to believe yourself, that your need to rule is altruistic. It seems to me that very few terrible people realize that they’re terrible.

Time defeated him first – everything followed.

__________________________

Eventually, “I ain’t as good as I once was, but I’m as good once as I ever was” turns into “I can’t do that anymore.” It’s hard to know when that happens, though, unless you continue trying.

I’ve always enjoyed the genre of story where the old gunslinger, the old boxer, the old dog, etc., gets up for one last fight and goes down in a blaze of glory. If the old character wins decisively, then he/she isn’t at the edge, yet. There’s more story left to be told. If they lose decisively, then he or she is way beyond the edge and it’s more of a sad and tragic ending (and it’s probably a moment in someone else’s journey.) For the story to work, you need to dance around on that line.

Pro Wrestling handles these stories better than any other medium. Who among us doesn’t remember Shawn Michaels, with tears in his eyes, taking out Ric Flair and ending his career… then sobbing over him after. Give them both an Academy Award.

The unexpected gift was a goodbye.

____________________________

I debated over whether to flip “goodbye” and “gift.” I decided I liked it better this way, as it puts the motives and emotions of the person leaving more into focus for me. The person leaving is the one who defined the parting as a gift. But when you flip the two words, the focus moves onto the recipient. The recipient is the one who defines the characterization of the goodbye.

Language is weird.

The candle’s flame outgrew the house.

Occasionally I start talking myself into the notion that – hardships and all – pre-Industrial man was better off and more fulfilled. Then I think about how they lived in wooden houses and defeated the darkness and cold with candles, torches, and fireplaces, and I reconsider.

How much more common an occurrence were house fires five hundred years ago? Was the danger such that they were less common because teaching about fire safety was paramount? (These types of questions are how you lose an afternoon in a Google rabbit hole.)

You can google “the Great Fire of ____” (fill in the blank with your city) and usually pull something up. Assuming that you are not a believer in Tartarian Empire conspiracy, you might conclude that devastating fires were far more common in the not too distant past, precisely because if open fire and wooden structures. If you are a believer in the Tartarian Empire conspiracy, then you believe Great Fires were common in the 19th and 20th centuries because of a meticulous effort to erase our history. I suppose open flames and wooden buildings made that effort easier.

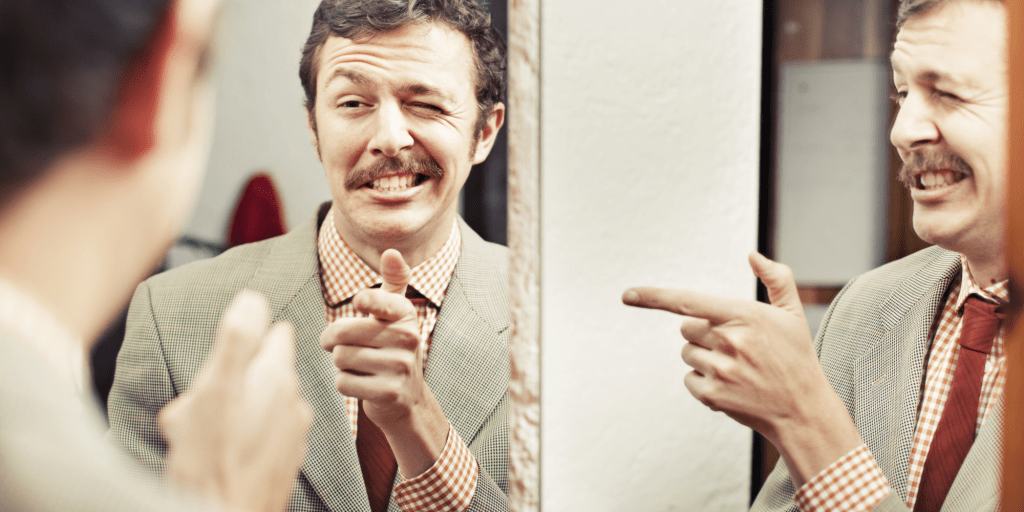

Egoism beget anxiety; anxiety beget egoism.

Is this a loop one can get trapped in? I think it’s sort of an easy thing to not notice “egoism” when it feels justified by something reasonable. If your mind is focused on yourself, because of a problem you have, it feels rational to focus on yourself in an effort to solve that problem.

But what if the effort to solve the problem is perpetuating it? The most content people I know think about themselves the least (or so it seems from outside of their brains.)